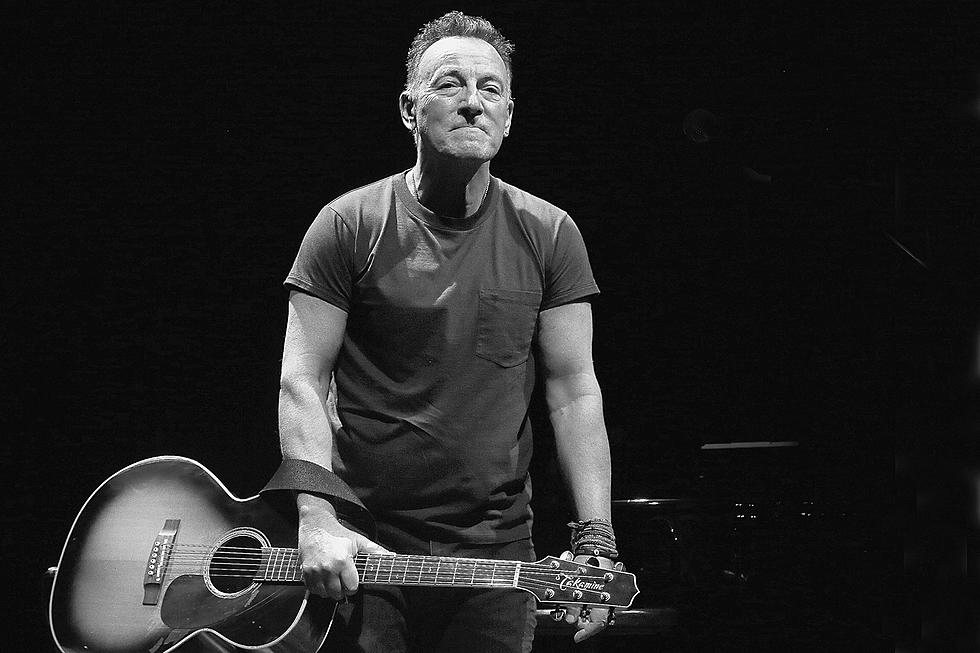

Bruce Springsteen Looks Back in ‘Springsteen on Broadway': Review

In Springsteen on Broadway, Bruce Springsteen accomplishes what few people — artists or otherwise — can: He distills his life’s work down to a cogent, two-hour narrative. That’s no small feat for a man whose career has already spanned half a century and has been shaped by a challenging childhood and an ongoing battle with depression.

At its core, the show is about “Growin’ Up,” a song that conveniently appears on the Boss' first LP, Greetings From Asbury Park, N.J. and kicks off the show, and how he’s learned “to live with what he can’t rise above,” as he later put it on “Tunnel of Love,” from his 1987 album of the same name.

He traces his roots — familial, geographic and musical — at once with broad strokes and discerning detail, addressing several great ironies of his life and career: Songs about speeding away like “Thunder Road,” “Born to Run” and “Racing in the Street,” for example, were written by a man who didn’t obtain a driver’s license until well into his twenties and who now lives a few miles from his hometown. Like so many Jersey shore grifters before him, Springsteen considers himself a fraud, one of two ideas that bookend the show. After speaking early on of the church down the block that his mom dragged him and his sister to every time the bells chimed for weddings and funerals, the lapsed Catholic closes the show with a prayer, as well what is perhaps the closest thing to a prayer for himself and his fans: his classic 1975 song "Born to Run."

But most telling in this tale is how his parents’ disparate personalities influenced his trajectory. Even though he writes so vividly about blue-collar workers and an indefatigable work ethic, Springsteen has never held a normal job. So where did it all come from? His parents. He famously feuded with his father, who suffered from an undiagnosed mental illness, well into adulthood, but it was his father’s language, uniform and dreams that Springsteen adopted in his own work. Always close with his mother -- a proud working woman who never complained, could talk to anyone and radiated optimism — he’s struggled to live up to these qualities all his life.

These stories begin as soon as he steps into the spotlight, in what at first feels too stiff and too scripted for such a spontaneous performer. But he quickly warms up, and it becomes a casual conversation; yes, he expects audience response, even on Broadway — “Okay, go crazy,” he says when he sits down to play “Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out” on the piano — but not too much. In contrast to performances on The Ghost of Tom Joad tour, which was playfully dubbed the “Shut the F--- Up” tour after a few less-than-genteel requests for silence, he now pauses, raises a hand to the audience and teases “I got this!” when they begin clapping along to "Dancing in the Dark."

Though he boomerangs between microphones — standing with his guitar or sitting at the piano — they are superfluous. He often continues his narrative, uninterrupted, as he walks from one to the other, and fans don’t miss a beat in the 975-seat Walter Kerr Theatre. It feels like an intimate gesture. The audience can hear each breath Springsteen takes, and every strum of his guitar, leading to a distinct desire for the detail-obsessed fans among us to shout “pick!” the way a young Springsteen yelled “stick” in The Promise: The Making of Darkness on the Edge of Town each time he heard E Street drummer Max Weinberg’s stick hit the canvas.

Of course, most of the work for the show was done long before it was even conceived. Much of its monologue is taken directly from his bestselling 2016 memoir Born to Run, and many of its acute insights undoubtedly stem from decades of therapy. Hardcore Springsteen fans already know the tales, whether verbatim or more generally, contained in this four-month Broadway run, and its songs are among his biggest hits and most autobiographical. But his life story is not the focus, except in how it has colored his work. He spends more time and attention talking about Clarence Clemons, the E Street Band’s late sax player, than he does his wife and bandmate, Patti Scialfa, who joins him onstage for two songs.

But make no mistake, the show is for the fans. The performance rests on the audience’s prior knowledge and — let’s admit it — adulation. It assumes much of the audience is has already devoured as much as they can of Springsteen's output and is there to grab whatever additional morsels they can. At least once he mentions “the book,” without establishing that he wrote one, and later includes Terry Magovern in a list of dearly departed friends, family and bandmates. Longtime fans will know the name — Springsteen’s friend-turned-personal assistant, who died in 2007 — but they are the same people who can identify Springsteen’s guitar tech, Kevin Buell, on the street.

Using Springsteen’s own math -- he says the magic of a rock 'n' roll band happens when 1+1= 3 -- Springsteen on Broadway, with its known stories and well-worn songs, is greater than the sum of its parts.