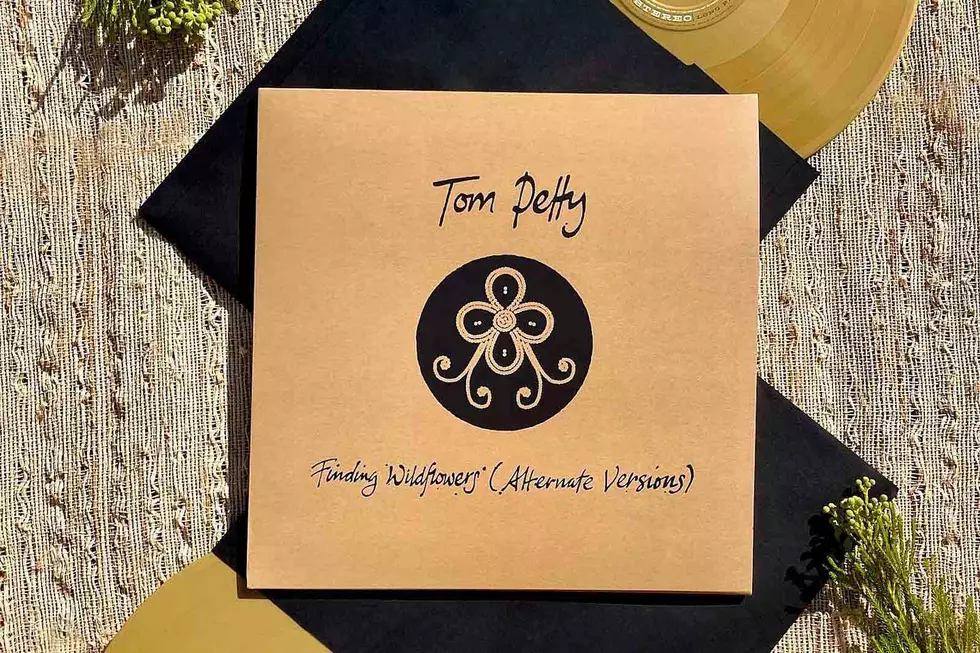

How Tom Petty Stripped Down for His Second Solo LP, ‘Wildflowers’

From a sonic standpoint, Tom Petty's recorded output from 1981 to 1991 is a study in addition, from the relatively stripped-down work he and the Heartbreakers turned out early in their career, to the more ornate approach they developed in the mid-'80s, to the layers of lush sound applied by producer Jeff Lynne on 1991's Into the Great Wide Open album.

By the time Petty settled down to start work on what would become his second solo effort, 1994's Wildflowers, it was time to start subtracting.

Commercially speaking, any tinkering with the Petty formula was a risky move. From the late '80s on, including his records with the Traveling Wilburys and his huge Full Moon Fever solo effort, he'd been omnipresent on rock radio, due at least partly to the stacks of harmonies and guitar jangle Lynne applied.

On the other hand, radio had changed quite a bit during the years he'd been away; the most popular new rock acts favored a rougher, rawer approach – and perhaps not coincidentally, that's exactly what Petty had in mind for Wildflowers.

A simpler sound didn't necessarily mean an easier songwriting process. In fact, while Wildflowers sounds a lot more informal than anything Petty had done to that point, it required a deceptive amount of creative focus. "It was a lot of work. Two years," Petty told Paul Zollo in his book Conversations With Tom Petty. "There's a lot more than came out. ... But yeah, I felt right in the pocket there. I was right in the zone, and I got a lot of good work done. We were very determined to bring that thing home."

"We" in this case included new producer Rick Rubin, who'd risen to prominence as a co-founder of the Def Jam label and helped break scores of hip-hop acts (including the Beastie Boys and LL Cool J) before branching into rock production for acts like Slayer and the Red Hot Chili Peppers.

Set up at Warner Bros. with his newly founded Def American imprint, Rubin reached out to Petty's manager, Tony Dimitriades, after hearing that Petty would be leaving longtime label MCA for Warners.

Petty and Rubin hit it off after spending a day in the studio together, then embarked on a long journey that would find Petty recording as a solo artist – albeit one who was still working alongside pretty much everyone in his band – for the second time in his recording career.

Watch Tom Petty Perform 'You Don't Know How It Feels' Video

"I think that Rick and I both wanted more freedom than to be strapped into five guys. We wanted to be able to do whatever we wanted, really, as far as bringing in this guy or that guy," Petty explained. "With a Heartbreakers record, you can't bring in a different bass player or a different drummer. So, I wanted that freedom, and we did play with a lot of different musicians, and we even did a lot of trial and error with different musicians, auditioned people for the record."

Calling the sessions "just a casual process of getting together every afternoon for two years," Rubin told Rolling Stone that he had a fairly clear idea of what he wanted Wildflowers to sound like from the beginning: "I just hoped we could have songs as good as Full Moon Fever, but with a more rock 'n' roll, more personal approach, as opposed to a pop presentation."

"It seemed much more natural to the Heartbreakers than the stuff that was done with Jeff. He has a strong personality, he's brilliant at what he does, and you know it's Jeff Lynne," longtime Heartbreaker Benmont Tench told UCR's Matt Wardlaw. "The 'Wildflowers' record was more of a reset for Tom and for [guitarist Mike Campbell], who'd been working so closely with Jeff, than it was for me. 'Wildflowers' sounded, for me, more like the Heartbreakers.

"I think it's one of the best things the Heartbreakers ever did -- my taste leans in that direction, sounding more like just two guitars, bass, drums, and piano," Tench added. "Even though that's a produced record -- great attention was paid to detail. But that's more where my sensibilities lie. The Jeff records are great; I'm not knocking Jeff at all. But I lean more toward the 'count four and play it.'"

But as the best bands know, before you can just "count four and play it," you have to really get your songs in order, and Rubin was also far more of a taskmaster than Petty had been used to.

"He pushed me, and I really think he got the best out of me. Sometimes he just made me downright angry," Petty recalled. "It was just, 'Write, write, write! Write more!' And he'd come to my house and want to hear all the demos. 'Okay, I like this one, I don't like this one, I like half of this one. Finish this. This is really good. Throw that out.' He was that way, very song-oriented, and really an intelligent guy. A bright guy, and I enjoyed working with him. We're still good friends."

It wasn't all happy vibes surrounding Wildflowers: Drummer Stan Lynch, who'd been an outspoken critic of Petty's decision to go solo for Full Moon Fever, would see his long association with the Heartbreakers end before Wildflowers arrived. It wasn't a decision that either Lynch or Petty arrived at quickly or easily.

Watch Tom Petty Perform 'It's Good to Be King'

The mood between the two had soured well before Lynch's eventual termination following the band's Oct. 2, 1994, show at that year's Bridge School benefit, and Petty later recalled that after Lynch's final session with the Heartbreakers, for the 1993 Greatest Hits bonus track "Last Dance With Mary Jane," he left the studio without saying goodbye.

Admitting that, in his view, Lynch "never got over" not being invited to play on Full Moon Fever, Petty described his longtime drummer's firing as more of a mutual parting of the ways.

"Stan and I always had a turbulent relationship, but it was part of the magic. But there came to be real tension in the music. We honestly couldn't function with each other," he recalled. "I did get mad at one point and sort of pushed him, but I didn't fire him. Stan needed a little shove to make that decision, and I only shoved because of the pain I could see him in, which eventually was causing me pain and problems. In a way, Stan left the room without saying goodbye. I said to him, 'Hey, listen, man, a 20-year run is pretty good.'"

Lynch's replacement in the Heartbreakers lineup, Steve Ferrone, arrived during the Wildflowers sessions, and Tench told UCR that his addition to the mix made a fundamental contribution to the album's departure in sound, saying he "made a major difference in the feel and the groove -- it's a drastically different feel."

On the charts, the results weren't drastically different at all. Released Nov. 1, 1994, Wildflowers peaked at No. 8 on Billboard's Top 200 Albums chart, outpacing Into the Great Wide Open by five spots and surpassing its double-platinum certification by a million copies.

And while the album had only one pop hit, the No. 13 "You Don't Know How It Feels," it extended Petty's dominant stretch at rock radio, where that single joined "You Wreck Me," "It's Good to Be King" and "A Higher Place" in heavy rotation. After two years and no small amount of turbulence, Petty had yet another hit – and an album that many continue to point to as a highlight in his extensive catalog, including the late Petty himself.

"It's my favorite, I think, of all of them," Petty admitted years later. "I think it's my favorite, just overall. We intended it to be two CDs, and we worked almost two years recording it and writing it. I wrote a hell of a lot of songs, and we recorded 21 or 22. ... I think, looking back over all our work, to me, it's just one of the most satisfying things. You know, I like other ones. But that one is the most me, I think. That's me. That's where I live musically."

Tom Petty Albums Ranked

More From 96.5 The Walleye